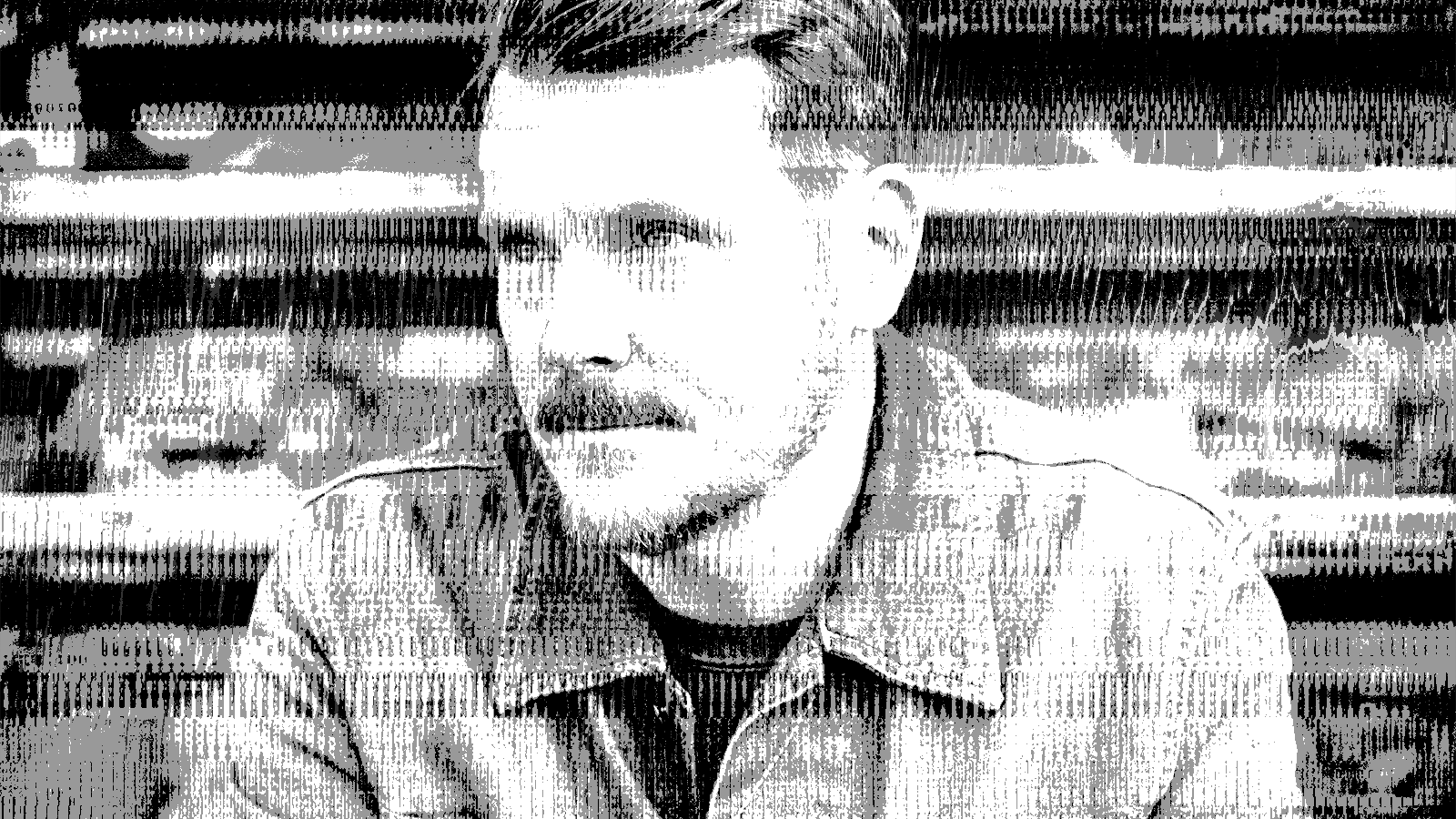

INTERVIEW: Andrew Forbes, Author of The Utility Of Boredom

garbageface's note: Andrew Forbes' The Utility Of Boredom is a quiet triumph. ostensibly, it's a book about baseball. but in so many ways, it's barely about baseball at all, and more about the contours and edges around baseball, and about how the game sits around the edges of life. i learned from a blurb about this book that baseball fans are sometimes called "seamheads" — referring, i think, to the way a baseball is stitched together? i found the term charming, because this book is very much about the seams.

as with my interview with Debbie Urbanski, the audio version of the interview contains a backing "soundtrack" — in this case, some baseball stadium ambiance culled from one of my favourite open source sound libraries, freesound.org. if you don't like it, cool. you can read the interview in text form below, and check out a longer pre-amble to some of the themes here.

EVERYONEISDOOMED: I'm holding The Utility Of Boredom... If you had told me a few years ago that 1) I would read a book about baseball, and 2) that I would enjoy it so much, I would have thought for sure you were talking about a different person. Not me, right? But I really did enjoy this a lot, and then had this weird experience. I got this at Take Cover Books...

Andrew Forbes: Good, bless them.

EID: ...yeah. And it was cool, because I go there a lot. I have peculiar book tastes, and I've usually ordered something in and I don't often do a lot of browsing. But this time I did, and saw your book on the table or on the shelf somewhere, and I thought: You know what? There's a lot of people in my life who love baseball... And I love them! I want to, I want to understand them...

AF: Better understand the illness, yeah.

EID: ...So I grabbed it, and I was looking at the back, and I saw that you were from Peterborough, Ontario. And after I read it, I thought, I'd really like to talk to this guy. So I looked you up on Instagram, and I was and I was like, Oh, we're already following each other. Felt like a very Peterborough moment... so thanks for sitting down and talking to me. We already knew each other, apparently.

AF: Yeah, Peterborough is a closed containment unit sometimes, right?

EID: Yeah, and so I wanted to talk to you about baseball, which, again, I never thought I would want to, but I really do now. And I found this book so engaging, and it so wasn't what I expected. Maybe you could start by telling the folks listening — probably some who you know! — how did you get into baseball?

AF: I think it's a pretty common and bland origin story in that my dad watched it and I played it. We had, you know, my friend Mikey, next door when we lived in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. We both had the big, giant fat plastic bats and tennis balls, and there was a spot in between the two houses, and we would play there kind of uphill. It was watching Blue Jays games and watching Expos games with dad and trying to figure out what they were doing and what was going on. And then it was the visual ephemera of it, baseball cards and the jerseys and the caps and the posters and it was going to a game.

When I was younger, we went to a game in Toronto at Exhibition Stadium. And what I remember about that is being very hot — but then a few years later, we're probably talking, I don't know, '85-'86 going to a game at Olympic Stadium in Montreal. And the the kind of mind expanding experience of walking through the tunnel and taking in the enormity of that space with the absolutely glow-in-the-dark green astroturf and that enormous roof. And then watching the Expos play the Cubs, I was hooked.

You can fill in your own experience here for whatever still kind of scratches your itch. But I think for baseball, it just kind of hit me at the right time, and it had the right, stimuli associated with it and and now, probably now, it's a matter of being trying to maintain contact with my childhood self. There's a bit of Arrested Development involved, for sure.

EID: One of the things that you talk about in the book is... well, you mentioned a couple other sports. One of the sports that you mentioned is hockey, and that hockey is just so materially different, experientially different, than baseball. Say more about that?

AF: Hockey is fast and is always fast, between timeouts, between whistles. It doesn't give me the same space to breathe that a baseball game does. A baseball game is slow. I mean, the title of the book is The Utility Of Boredom. The baseball game has a lot of inaction punctuated by moments of furious activity. Those valleys make those peaks that much more remarkable. I like hockey, but it's never sunk its claws into me the same way baseball has, because it's just sort of rhythmically I'm not in touch with it the way I am with baseball.

EID: But football had. You mentioned in our in our DM exchange that you that you used to be a big football fan, and I want to get to why you're not anymore. But football also strikes me as — it can be slow. The last two minutes of a game can take an hour. And one of the things that you talk about in relation to baseball that I found fascinating was its relationship to radio, and that's one of the things about football that I can't... I can't imagine listening to a football game on the radio.

AF: Well, I will counter that though, in that my first football love, growing up in Ottawa, was the Ottawa Roughriders CFL team, and Dean Brown was the voice on CFRA radio. He's still doing radio for the senators. He does the hockey games, but Dean Brown's voice on the little clock radio next to my bed calling CFL games was was a big part of it, and it is different. It doesn't have the rhythm, it doesn't have the same sort of elasticity, and it doesn't have the same restraint and release that baseball has. But I did form some very passionate attachments to that voice, that game on the radio when I was you know, 8-9-10 years old, listening to those games. So I don't know. I've listened to some other football games on the radio. It's not as perfectly structured for radio as baseball is, but it can still be exciting.

EID: People talk about radio as theater of the mind. And I've listened to hockey games on the radio, but the way that you describe the relationship to radio and baseball is... it gels a lot more. And you also describe it as being part of a daily routine, like doing the dishes...

AF: Well, baseball's everydayness is another part of it that appeals to me...

EID: almost literal everydayness!

AF: Once spring training starts, there are only a handful of days between then and late October, early November, when there isn't a baseball game. Like a literal handful. We're just coming out last week, the all star break in which there's, what, two, three days without baseball. I had difficulty with it [laughs]. especially because, as you and I were talking, I'm up at the cottage last week, and doing stuff around, and normally I would just kind of have a baseball game on in the background whenever there's one on. You know, it's a companion. It's a soundtrack. It's something that has connected to that love of the person that I was as a nine year old. It's a companion and it keeps me a sort of happy, gentle company. It doesn't ask much of you. You can not pay attention and still kind of get the vibe.

EID: I love that you use the word vibe, because that's something that the people in my life who love baseball have have talked about: that it's so often less about the action and more about the vibe.

AF: You can't help but kind of make the associations to summer and to sunshine and to relaxation and to the company of the people that you love, and to me, it fills a big need in terms of ritual, there's an awful lot about it that is ritualistic, that's repetitive, that just seems to soothe something in my otherwise troubled brain.

EID: Were you ever a religious person?

AF: No, not per se. You know, my family dabbled in church, going from time to time. I was aware that there was a history in the family of being of being religious, especially small town, Nova Scotia, Presbyterian on my mother's side. So, you know, lots of guilt, without the without the release of confession, which is great. You should probably be doing something right now to prove that you're worthwhile as a human!

But no, I wasn't religious. You know, I've been curious about religion and its place in people's lives. I've certainly done a lot of reading about it, and I recognize... My wife's family's a big PEI Irish Catholic family. I get the appeal of something that feels like community, that provides structure. And I think that, you know, we're not really in a post-historical moment, but it does feel that way sometimes, and we're all kind of constructing our own meaning, if we're lucky, if we're living above subsistence. For me, yeah, baseball fits a kind of a ritualistic... it takes up an awful lot of the year, and the other half of the year is spent waiting for it and thinking about it and remembering it. That is a lot like religion, you know.

EID: Yeah. And the way that you describe it in the book... because it's not just that you describe the the ritualistic aspects of it, but you're also talking about the ballpark as a place, and what, what the ballpark means, sitting in the benches. There's a chapter where you talk about the grandstands, which are different than a big arena ballpark, with the nicer chairs. You're sitting on these benches right next to people. You're maybe touching the person next to you.

AF: Frequently We can talk about trough urinals and some of the old ball parks.

EID: And so that comes out too, in the sense of like a place of worship... worship sounds very lofty, but...

AF: yeah, a place of community, a place of gathering, right? A place to be, a place where people gather in numbers to collectively be put in touch with something other than their daily lives, I think, at its simplest, simplest sense.

EID: Yeah. My brain keeps wanting to compare it to football. I used to love sports when I was a kid, I just loved it so much. And then as a teenage, artsy kid, I fell out of love with sports because everyone who hated me loved sports, so I really stopped enjoying it. And, you know, I kind of wrote all sports off as kind of stupid. And sometimes when I watch sports now, specifically football, I still think, gosh, this is stupid. But I want people to have their stupid little things that they love, you know? I really want people to have those in, like you're saying, a world where constructing meaning has become increasingly difficult. Meaningless things can mean so much.

AF: Yeah, they can. You know, it's a strange time, for a number of reasons. There's a literal genocide by starvation occurring, right? There's a war on our trans brothers and sisters. There is an authoritarian government in charge south of the border that has changed that culture so completely in six months. It's unbelievable. So it can feel, I don't know, guilt-inducing sometimes, to have these distractions. But I think that, first of all, I would point out that the world has always been on fire. I'm not saying that these things aren't terrible. They are, but the world has always been on fire. There was, you know, there was a pennant race, you know, during the Holocaust. But these things, I think, if we put them in the proper place in our lives, can help us recharge. They can bring us in touch with something that feels energizing... and can sort of arm us for the fight.

EID: Thinking back to the arena, and the way that a ballpark is set up, I think there's something there. I know that most stadiums and even hockey rinks are technically circular. They're oval, there's no break in the line around the audience, around the playing surface. But there's something about the ballpark being almost much more of a literal circle that feels symbolic in a way.

AF: A lot of the classic ones weren't, or aren't, or have since been sort of retrofitted to be that way. There's a an architecture critic named Paul Goldberger, who has some really interesting things to say about the way that the ballpark places a pastoral setting amid an urban one, and the way that those two things play at each other and tug at each other and create tension. Going back to that first image of seeing that — it was plastic, it wasn't real grass — but seeing that green expanse in the middle of a sort of technological marvel in the middle of east end Montreal was a formative experience for me. And I think that there's something in our brains which really does... Arenas in general, but the baseball field, the baseball stadium, or ballpark... Specifically, there seems to be something about the way that the juxtaposition of the natural and the pastoral rubs against the built world, the built environment, and invites people in to sit and take that in, that seems like it kind of bypasses some of our cynicism and hardwired doubt, you know.

EID: Yeah, and there's a part in the book where you, I think you mention... I don't know if you actually say the words Field of Dreams, but you kind of allude to the idea of the ball players literally coming out of the cornfield.

AF: Right? Yeah. There is something. There's a lot of writers who spilled a lot of ink — and I'm part of that, for better or worse — talking about the seemingly magical qualities of the game. It's almost certainly trial and error / dumb luck, that things worked out sort of geometrically, and the physics of it, and everything worked out to make the game as perfectly balanced as it is. But when you take it in as a spectator, it can be difficult to brush away the suspicion that there's some magic involved.

EID: Why did you fall out of love with football?

AF: I wrote an essay around this somewhere. I don't know where it is, somewhere online... But I got uncomfortable with how chummy football, specifically the NFL, had become with the American military industrial complex. My team, when I was a rabid fan, was the New Orleans Saints. There was the bountygate scandal, where it was revealed that members of the of the New Orleans Saints were being paid to, you know, injure other teams' quarterbacks and things like that. And that is barbaric, but it's also, it seems to me, exactly what they're being paid for anyway. There was, there was a kind of hypocrisy about it, and I tentatively stepped away and then found that it didn't really... I didn't miss it. It made it easier to just make the break final.

I should be clear, I don't have any... I know lots of people who are very fervent football fans. You know, I mean, whatever gets ya.

EID: It's funny, though, as you describe it, I think part of what has made me gravitate towards football is just how honestly brutal is. It is just a brutal sport. I mean, they try and make it safer but there's only so safe you can make it. And like you're saying, I mean, the guys are being paid to hit,

AF: To injure one another.

EID: Not to injure one another, quote unquote, but if that happens...

AF: Yeah, it's part of the game.

EID: ...Then no one is, you know... no one feels particularly bad about it. In fact, lots of historical cases where people have been severely injured and the people who injured them did not feel bad in any way. And I realized, as you were talking about the ballpark, that my team growing up, the Raiders, when they moved to Oakland...

AF: Just win, baby.

EID: Yeah, just win, baby! And before they moved to Vegas, the arena that they were playing in had a ball diamond on it. I went to go see a Raiders game where they're, you know, halfway through the field they have to run across the ball diamond.

AF: Yeah, across the cutouts. That used to be so much more common. They almost never share stadiums anymore, but that used to be so common.

EID: And I think one of the things that I appreciated in the book is that you don't give baseball a total pass. Like all of the words that you're describing, like, pastoral, magical... There are these wholesome qualities about baseball.

AF: Seemingly.

EID: It's not a violent game. It's not supposed to be a violent game. There's not violence built into it like there is with hockey or football. It's not as constantly physically exhausting as soccer. There are these tremendous peaks and valleys, which I want to talk about a bit more. But one of the things that I appreciated is that you don't just talk about baseball as if it's perfect.

AF: Yeah, that would be a pretty dull book.

EID: Well, I don't know, the parts where you talk about baseball being magical and wholesome and lovely are very well put. But tell me more about what you think baseball could do better.

AF: I think that there's a lot of different ways to tease that out. One of the things that I recognize is that baseball with a small b is distinct from baseball with a capital B, and the latter being the sort of, you know, American based corporate entity that seeks to control all aspects of the game — Major League Baseball and all its subsidiaries and all of that stuff. And they've done a good job for a long time of fucking it up, right? They are self-satisfied, moneyed men who make decisions for the wrong reasons, right? That's true everywhere. The game itself, that somehow very similar men were able to invent, is a distinct thing to me, which I don't have many bad things to say about.

But, I mean, look, it's a game that's been full of violent, alcoholic racists. It's a game that has not made room for women. And these things are changing slowly, but, you know, it's got a very checkered past. It was synonymous for much of its early history, despite its efforts to paint itself as a gentlemanly game, quote unquote, with real visceral violence and real sectarian animosity. You know, all these things were wrapped up in it. And one of the things I love about the game is that you can use it as a lens to examine a whole lot of history — social, economic, the history of labor relations, as I do in a more recent book. It really does provide an interesting glimpse into history. It's kind of a silo. You can look through baseball history and have access to all these different things.

I also coached youth baseball for a couple of years — assistant coach, I should point out, which is a great position to be in, because you're not ultimately responsible for everything, but you still get to encourage the kids and have fun, put on the uniform, and stand on the diamond and everything. It's great. But yeah, certainly there are aspects of the culture that are that are less than healthy as well, right? It's like any sporting culture. It's still got a ways to go. Hockey, certainly, that's true, and it's true in everything. My kids have played volleyball and Ultimate Frisbee and all kinds of things, and there are elements of all of that in every sport that need to be addressed. Absolutely. So I make a very clear distinction in my mind, which I try to articulate, between baseball the business baseball, the corporate entity, baseball the the vehicle of American imperialism, and the game that you would play with your buddies when you're 12 years old and you find yourself with a field in a vacant afternoon.

EID: There are a couple of chapters in the book that are about very specific players, not necessarily the most famous ones, either.

AF: Good stories.

EID: Good stories, and their careers and and how hard it is to make a career, how hard it is to be at the top, or to try and get to the top, and how fleeting it is. What you alluded to — these dynamics are kind of present in every sport. I feel like, when you get, you know, a group of several hundred men in one place, there's gonna be some real pieces of shit in there.

AF: That's typically the way, yeah, yeah.

EID: But there's one story in particular that I keep thinking about in my head about, and I'm forgetting the guy's name. Apologies for that, but there's a you're working at a record store in Ottawa.

AF: Ted Lilly.

EID: Ted Lilly! And he comes in, he's looking for a CD to play in his car, and he buys a couple of CDs, and they don't work in his car. And then you have this moment with him out in the parking lot. And he's playing on the Ottawa team...

AF: yeah, he's on his way up to the Expos eventually, is the goal, so he's playing minor league baseball for the Expos team in Ottawa.

EID: Yeah. And he asks you why more people aren't coming to the games. And my heart broke then, too. You say that he broke your heart by asking you that.

AF: Yeah.

EID: And I felt like I understood exactly why, yeah. But maybe you can, maybe you can tell us more.

AF: Ted Lilly, if any of your listeners remember him, it may be for the time that he apparently got into a fist fight when he was playing for the Blue Jays with the manager in the tunnel after... Ted felt he was prematurely removed from a game, so he and John Gibbons went at it. But, yeah, very capable, left handed, curveball specialist, bounced around quite a bit, but had a decent career in the big leagues. You know, there's a very small handful of people who will be Babe Ruth or whatever, Willie Mays. And most people are content, maybe not content, but recognize that they are lucky to be capable and able to play professionally, the thing that they love doing. And I would put Ted Lilly in that second category. But when he was a minor leaguer, he was assigned for a season to Ottawa, the Ottawa Lynx. I was living in Ottawa, and I was working at CD Warehouse not that far from the stadium, and I was still a fan.

And for a very brief backstory here, the history of minor league baseball in Ottawa is like great excitement followed by kind of indifference, followed by teams leaving town. So when the Ottawa Lynx debuted in the early 90s, they were the hottest ticket, man. They sold out their 10,000 plus seat stadium every night, and by '96 they won a championship. And then, as things wound down after that, for a number of reasons — the Senators were better people were more interested in the Springtime... in playoff hockey and things like that — so the attendance dwindled. And by the time Ted Lilly got there... You know, a 10,000 seat stadium is a third the size of the smallest Major League stadium, but it is the biggest minor league stadium, right? These 10,000...

EID: 10,000 is a lot of people.

AF: It's a lot of people. And when there's only 500 people in the 10,000 seat stadium, it looks terrible. So there were a lot of nights like that. And, I mean, there's things that contribute to that. It's cold in Ottawa in May. A Tuesday night in May, early May, it could be five degrees Celsius. And only idiots like me are sitting there.

So yeah, Ted Lilly came in and he wanted... it was The Best of John Mellencamp, or John Cougar Mellencamp, however you wish to remember him. Not that he's dead.

EID: He's still alive!

AF: Painting, from what I understand, he's a painter. And so Ted Lilly bought the CD, and I thought this guy's got an accent. I didn't know who he was, but he had an accent that. I think he's from California originally, but he sounded American, southern, maybe. He brought it back in and said, this doesn't work. So I exchanged for another one. We did this a couple times, and then I said, "Can I see it?" You know, it was a slow day, maybe.

So we go to the parking lot, and the car that he's putting these CDs in is a blue Ford Mustang with California plates. And I got curious and said, "Do you mind if I ask essentially, what the hell you're doing in Ottawa?" And he said, I'm playing baseball. And so then we got into it, and he told me a little bit about what he was doing and who he was, and I realized I'd seen him pitch and everything. And then he turned to me and he said, "Can I ask you, why aren't more people showing up?" It was like, I wish I could... You're playing baseball in a hockey town, buddy.

EID: What it brought up for me, was that... I'm an independent DIY musician, so I've played in rooms that have a lot of people in them, and I've played in rooms that have no one in them.

AF: I'm an independent DIY author.

EID: There you go.

AF: I've read to rooms with nobody in 'em.

EID: And the one of the things that I don't think people often think about when they're spectating is that the person who's performing, whether it's reading or playing a game or whatever, is having their own experience. Ted's out there on the field, and his point of view is very different than the point of view from the stands. He's looking at the stands and seeing, you know, 85% empty seats, and going, I'm in the minor leagues, and no one cares.

AF: Nobody cares. Sometimes related. you look at the guy on the mound, the person performing whatever athletic feat, and all you're measuring is against your expectations of how they'll do in this moment. And you're not taking into account the tens, literal tens of thousands of hours that got them to this point, the struggles they've endured, and what still stands between them and so called success. I think most of the stories that appeal to me about, well, anything, but about sport and about baseball in particular, are the ones that humanize the whole deal. And that was a very humanizing moment. As you think this kid, he got drafted, he got his bonus, he on his way to the majors, he's gonna have a career, but he's looking around like nobody cares. Nobody seems to care, right? Yeah, it's a very humbling, humanizing and true moment, I think, which is why I recognized, when I was writing that piece that I needed to amp up the heartbreak.

EID: You really did, you really did.

AF: The writer named Steve almond once told me, "wherever it hurts, slow down." Yeah, slow down.

EID: That's great advice.

AF: Yeah, it is good.

EID: So now, maybe we can slow down the hurt a little bit. So after I read this, I saw you were from Peterborough, I looked you up. I saw that there were a couple other books that were maybe about baseball. They looked like they're from the same series. And I looked up more of your work, and I was like, this guy's written a lot about baseball. He didn't just write a book of essays about baseball and then move on to his true passion, which was something else. It was like, no, this guy has written a lot about baseball, and I don't know if you want to talk about if you do other work... So many people who I know who are passionate about something and do it because they just love it so much. A lot of musicians that I know, even really successful touring musicians, when they get off tour, they got to work at the whatever. So what is it like being a baseball writer? Not that that's all you write about, but that's a lot of what you write about.

AF: I mean, look, I'm in the position where I have zero expectations about making this lucrative, or being successful, or whatever that looks like. I do it because these things won't they just kind of don't leave me alone. You know, there was a point where I thought I was done writing about baseball, but then it just kind of... Nope. We're not done with you. But, yeah, I've kind of alternated baseball and non baseball books. The first book I published was a book of short fiction. Nary mentioned baseball in that...

EID: ...but a couple of mentions.

AF: The book is called What You Need. I don't think there's any mention... Oh, well, there might be, but they're color, they're not the point of the whole thing. So that book, short fiction, was out in the world. I had a publisher, a small indie publisher at the time, based in Marmora, Invisible Publishing and it was one of the things I was doing to fill my time. Other than that, there were some other people I'd met in the writing world who were similarly interested in a Canadian approach to what we were calling literary sports writing. So it didn't matter what, whether it was the figure skating you'd done when you were nine years old, or what, we published pieces about bocce. Like we wanted to be a place where Canadian writers who had some experience with a sport could write high quality, deeply felt pieces about about whatever they perceived to be sport or leisure. And I would also write baseball stuff. I'd write other stuff too. There's basketball stuff on there — one of the other things that keeps me awake at night is the New York Knicks. So there were some pieces about the Knicks.

But yet, somebody at the launch party here in Peterborough — might have been Toronto — jokingly said, "you should collect all of your baseball pieces and publish a book." And my publisher at the time, Ash is her name. She was the publisher of Invisible Publishing said, "yeah, I'd kind of be into that." And before you know it, we were just collecting these pieces and mashing them together into what you've read there as The Utility Of Boredom. So it was a collection of sort of disparate pieces, whatever was tickling the baseball part of my brain over the course of a few years. And I think I thought I was maybe done with it at that point. And then I published another book, short fiction.

And then my very favorite baseball player of all time, Ichiro Suzuki, announced his retirement, and I was like, Oh, I'm getting pulled right back. So I wrote a book of essays, primarily about Ichiro's impact on my life, and kind of the things that he inspired in me and the way that his career moved in parallel to my my life, my biography. So we published that. And then I published, I can't remember what next, a couple more things of fiction. And then I found another interesting baseball story, a guy named Hub Pruitt who pitched for the St. Louis Browns in the 1920s who seemed to me to be an interesting avatar of a very peculiar relationship between sport and labor. So I wrote a whole book of essays about the relationship between labor and baseball specifically, and that came out.

And now I'm working on things that are not at all baseball related, but you know, in a way, sometimes I think that there's absolutely no crossover between the audiences, however minuscule the audiences are for this stuff — and other times I'm confronted with evidence to the contrary, which is neat, but I think of them as different streams. And baseball is... as long as people will let me, I love doing it. I love the research. I'll do several years of research because I love looking in old newspapers. As long as people give me the opportunity to do it, I'll continue to do it, while also harboring other literary ambitions that don't mention baseball.

EID: I mean, I guess what I'm wondering as well is, is this a living or is this a passion? Or both.

AF: Who can making an actual living in Canadian literature? I'm sure Margaret Atwood's doing it. Not many other people that are doing it, even the writers that I know who make a living writing for television, things like that. They have side gigs you can patch together an income from. Frankly, I'm looking at quantity over quality. Seven books in 10 years and, you know, there's a passive income aspect to that. I'm kind of joking, but I know,

EID: I know what you mean.

AF: Yeah, there's a passive income quality to that. And we do live, thank God, in a quasi socialist state when it comes to arts funding, certainly as compared to our American friends. So if you know where the funding bodies are and how to reach them and what they're looking for, you can string it together. I mean, I'm driving a minivan.

EID: One of the things that you that you mentioned there — you talk about feeling like you're done writing or you have been done with it and, or almost like, the sense of like you've said all you needed to say or wanted to say. And it's one of my favorite things about writing, and about writers, is that when you really care about something, it feels endless, like you can just keep going and going and going. It is one of the things that I got from your book. I mean clearly you love the game, but also there are these moments in the book where, it might be a split second, but time really unfolds across pages. I mean, the book's called The Utility Of Boredom. And you talk about how baseball has these intense moments of action that might last literally, like less than 30 seconds, 15 seconds, maybe, depending on how long the ball takes to get from right field to home. And then there are these long valleys of not much happening, and that seems particularly well suited to writing... but it's hard to when someone doesn't understand it.

I think I understood baseball a lot better when I was a kid, and then I stopped understanding it, and now I'm starting to understand it again. It feels good. But I guess, I do want to get your thoughts on, what does it mean to love something that people don't understand? You talk in very sweet terms about your wife — at different times in the book, your future wife — how she seems very tolerant of baseball. Maybe tolerant is too strong of a word. She seems kind of in a position that I feel like with people in my life where I want to love it because they love it, because it means so much to you.

AF: I think, first of all, when it comes to coming back to something, There's a quote. I'm not sure who it originated with. I know it from the writer, Richard Ford. You have to write about those things that cause a commotion in your heart, the thing that continues to irritate you means that you're not done with it — and by irritate, I mean, like scratch at you, not piss you off, necessarily. But I think that there's two ways to look at the things that I write, and that's that I am, both writing for a very large and healthy community of people who will read anything with a baseball on the cover. It's a massive community, really, in the U.S. and Canada. And then I'm also writing for people who, as you say, maybe don't share the illness or the passion, but are curious about it, or have someone in their life who they want to understand better. I think I reasoned long ago that the best that you can do is... I'm not trying to convert anyone. The best that you can do is lay out your argument and present it with care and precision. What it is that makes this thing important to you, and whether or not they adopt it, that's really kind of immaterial.

I also think that, for most of my work that is about baseball, quote unquote, baseball's kind of the setting. I really do think that the subject is effort and love and community and things that everyone understands, whether or not they know what you do in a 3-0 count, you know. I hope what I'm doing isn't evangelizing. I hope what I'm doing is just praising.

EID: I like that you use the word convert.

AF: Well, there's that religion again. It's a commitment though, right? It's a commitment to be really interested in something like baseball. This is a qualitative statement, but football: two, maybe three days a week, right?

EID: If you're only interested in following one team, it's once a week.

AF: If you're a Bills fan, it's either Monday or Thursday or Sunday. And that's it. I get it.

EID: It feels like every game is consequential, and it is in a lot of ways... like, 1/10 of the number of games.

AF: Can I say part of it is for me, growing up with my dad was and remains a big football fan. Loves football. yeah, and that's where I got it from. His thing was Sunday. The pregame started at noon, and he was watching until 60 Minutes came on. I can't imagine a) being content to sit still that long and b) getting permission to, you know — three kids and things to take care of. So that part of it seemed, when I was questioning my football fandom, it seemed kind of like a vestige of an earlier model of living, a few decades removed from where I live, let's put it that way. And not everyone does it that way, but that was certainly a common thing for for people that I knew growing up. You were glued to it. And then Monday night, — they didn't have Thursday night games — but you also tuned in Monday Night Football. So I just it seemed to me... yes, baseball is six or seven nights a week, but... well, I guess that's really kind of that's more, isn't it? Well, it is.

EID: But the with the way that you've described it. I mean, going to a game is different than listening to a game or watching a game. And I think there is a there is a qualitative difference between baseball several nights a week, and football all day long, Sunday. And like you've described, like the experience of watching a game is different. Yes, football can be slow in certain ways, but generally speaking, you've got to pay attention.

AF: Yeah, it's much more dynamic.

EID: Well, I think you convinced me that baseball is more dynamic. If we think about dynamics in terms of the breadth of what's happening... There are so many times I'm watching basebal were I feel like I want to check out, or I am checked out.

AF: I will also say a lot of it has to do, we talked about radio earlier, but a lot of it had to do with the quality of narration, the quality of the play by play. I'm old enough to remember when I was a kid, it was still John Madden and Pat Summerall on CBS doing games. And they were great. It was a conversation.

EID: And it takes a storyteller to fill the space, because there is so much space, and you you talk about how maybe that's been part of the reason why the game is so intensely... like statistics are brought in so intensely. You know, I've been watching the Tour de France, yeah, and that's another... a Tour de France stage is like four to five hours, and there are huge swaths of time where seemingly nothing is happening, and the announcers will start talking about the dinner that they had the night before, or, hey, they're cycling by this church, and, you know that they have an info sheet that's provided to them and probably part of the broadcasting deal, yeah, whatever. But, but it's really... it's nice! You're kind of engaged in this sport, and then all of a sudden you're hearing a story about this small town...

AF: Fifteenth century church. And there are some people that have been very good at that historically. And baseball, as you suggest, has got the time, and as I've written, is has gives them the time to to perform. Vin Scully, who was the longtime Dodgers announcer and did a lot of national broadcasts as well, many of them from my youth — I remember his calls verbatim, and he worked alone. He didn't have an analyst next to him. For the most part, when he did the NBC games of the week, he would usually have Joe Garagiola next to him, but Vin Scully could fill a baseball broadcast six or seven nights a week for six months and still have things to say. And they were personal stories, you know, he would remember poems, he would describe in painterly detail, what it looked like as the sun went down over Dodger Stadium. You know, just fantastic. People who understood their role and painted a picture.

One of my favorite things still about listening to baseball on the radio — which is to say on an app now, but you know, you can choose any audio broadcast from all the teams — is at the start of a game, the good broadcasters — and they're not all good — but good broadcasters will, in addition to telling you what the weather is and everything, they will describe to you the uniforms each team is wearing: the Cubs in their gray road pants and blue tops with their blue caps, the the Mets in their home white pinstripes, you know, things like that. And it just, it seems to me that they understand their role as laying out all there is to be interested in for the listener, as though you were there. There is a history of play by play announcers so good that people would sit with transistor radios in the stands as they watched what was happening and listen to the description of what was happening.

EID: Well, Andrew, I don't know if you've if you've ever been a broadcaster, maybe not, but your book is just incredibly evocative. It's called The Utility Of Boredom. I'm holding it up as if we're on video. We're not on video.

AF: Show them the back!

EID: Thank you so much for talking to me today. Thank you for writing this book. I read it in a day, and it was a really, really lovely day.

AF: That's all the endorsement I need. I appreciate that.

EID: Andrew Forbes is a writer, who writes about baseball and other things, and lives in Peterborough, Ontario.

Ø